Prison Hunger Strike Heads Into Seventh Week

SACRAMENTO, Calif. (AP) — A hunger strike involving several dozen inmates inside California's prison system evolved Monday into a semantic battle between their advocates and corrections officials over how to define such an action.

Lawyers and advocates said that the roughly 70 inmates who have refused prison meals since July 8 want to start taking a liquid diet that includes fruit and vegetable juices, just as they said hunger-striking terrorism suspects being held at Guantanamo Bay are allowed to do.

But California corrections officials define fruit and vegetable juices as food, and thus would reclassify inmates as not being on a hunger strike if they started drinking them.

The hunger strike is being led by violent felons who are being held in isolation so they cannot mingle with the general prison population.

The strikers want to drink fruit and vegetable juices issued with prison meals or that are for sale in prison canteens as a way to prolong the hunger strike, their representatives said during a conference call with reporters.

"There are many different types of hunger strike," said Jules Lobel, president of the Center for Constitutional Rights, referring to the different standard he said is used at Guantanamo Bay. "How they define a hunger strike ought to be for the hunger strikers to define."

Lobel called the state's definition "a blatant attempt to make it as miserable as possible and to force these guys off the hunger strike." He is representing 10 inmates who have filed a federal lawsuit challenging prolonged solitary confinement at Pelican Bay State Prison.

The advocates and state Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation spokeswoman Terry Thornton said that inmates are allowed to take water, vitamins and electrolyte drinks and still considered to be on strike.

The 69 inmates who had refused other nutrition for more than a month as of Sunday are among 129 who had refused at least nine consecutive meals. The strike included nearly 30,000 of the 133,000 inmates in California's prisons when it started.

Advocates and prison officials are increasingly concerned that some inmates who have maintained the strike for weeks might die from organ failure.

California incarcerates more than 4,500 inmates in what are known as Security Housing Units, some because of crimes they committed in prison and others for indefinite terms if they are validated as leaders of prison gangs.

Four prisons have the units: Pelican Bay in Crescent City, Corcoran, California Correctional Institution in Tehachapi and Valley State Prison for Women in Chowchilla.

The highest-ranking gang leaders are held in what is known as the "short corridor" at Pelican Bay. Four leaders of rival white supremacist, black and enemy Latino gangs have formed an alliance to promote the hunger strike in a bid to force an end to the isolation units.

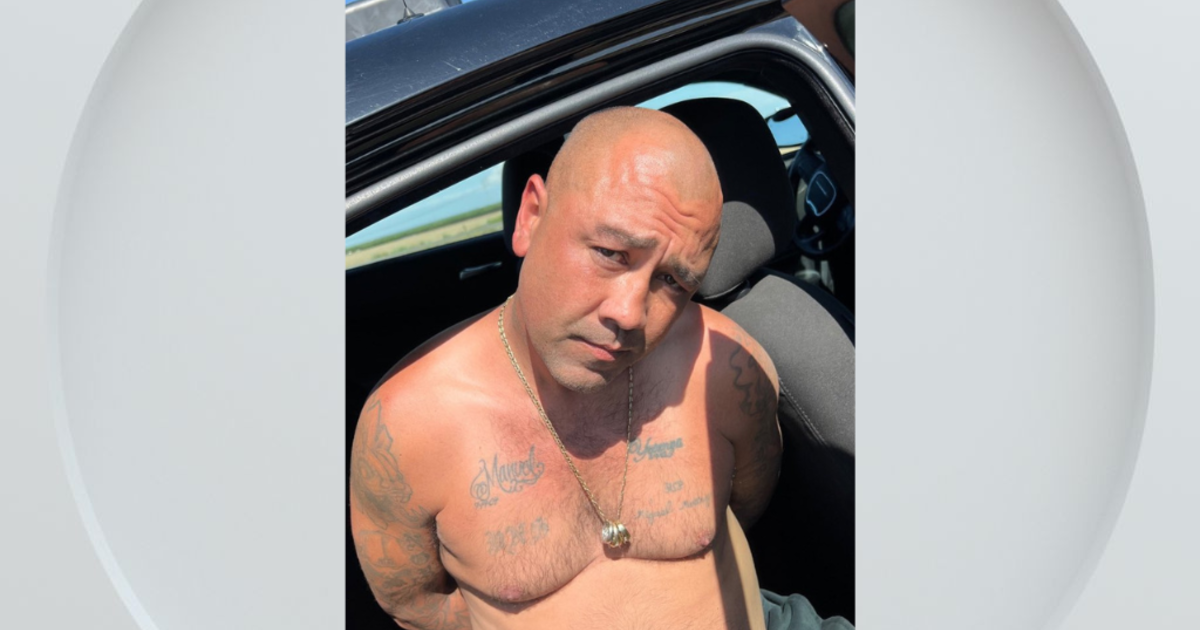

The four leaders who have signed letters on behalf of hunger strikers all are serving life sentences for murder and are accused of numerous attacks on inmates and employees in prison. One, Arturo Castellanos, was named earlier this month as an unindicted co-conspirator in a federal crackdown on the Mexican Mafia prison gang and a Mexican drug cartel. The indictment alleges that he continues to run a Los Angeles street gang from his cell.

"This indictment was pre-planned by the feds to be released during this hunger strike to discredit this peaceful hunger strike," Castellanos said in a statement released through inmate advocates. He denied having contact with or giving instructions to his old gang members.

After two hunger strikes in 2011, prison officials announced a new policy that makes it harder to send inmates to the isolation units and easier for them to earn release from them.

The department has reviewed the cases of 425 gang leaders housed in the Security Housing Units so far. Of those, 268 were being transferred out of the units and 125 had started the program that will lead to transfers for gang members who do not engage in criminal gang behavior.

Copyright 2013 The Associated Press.